Last week could have hardly been a longer one in Rome. On Wednesday, as yields on government bonds climbed to 7.48 per cent, Italy was staring down the barrel.

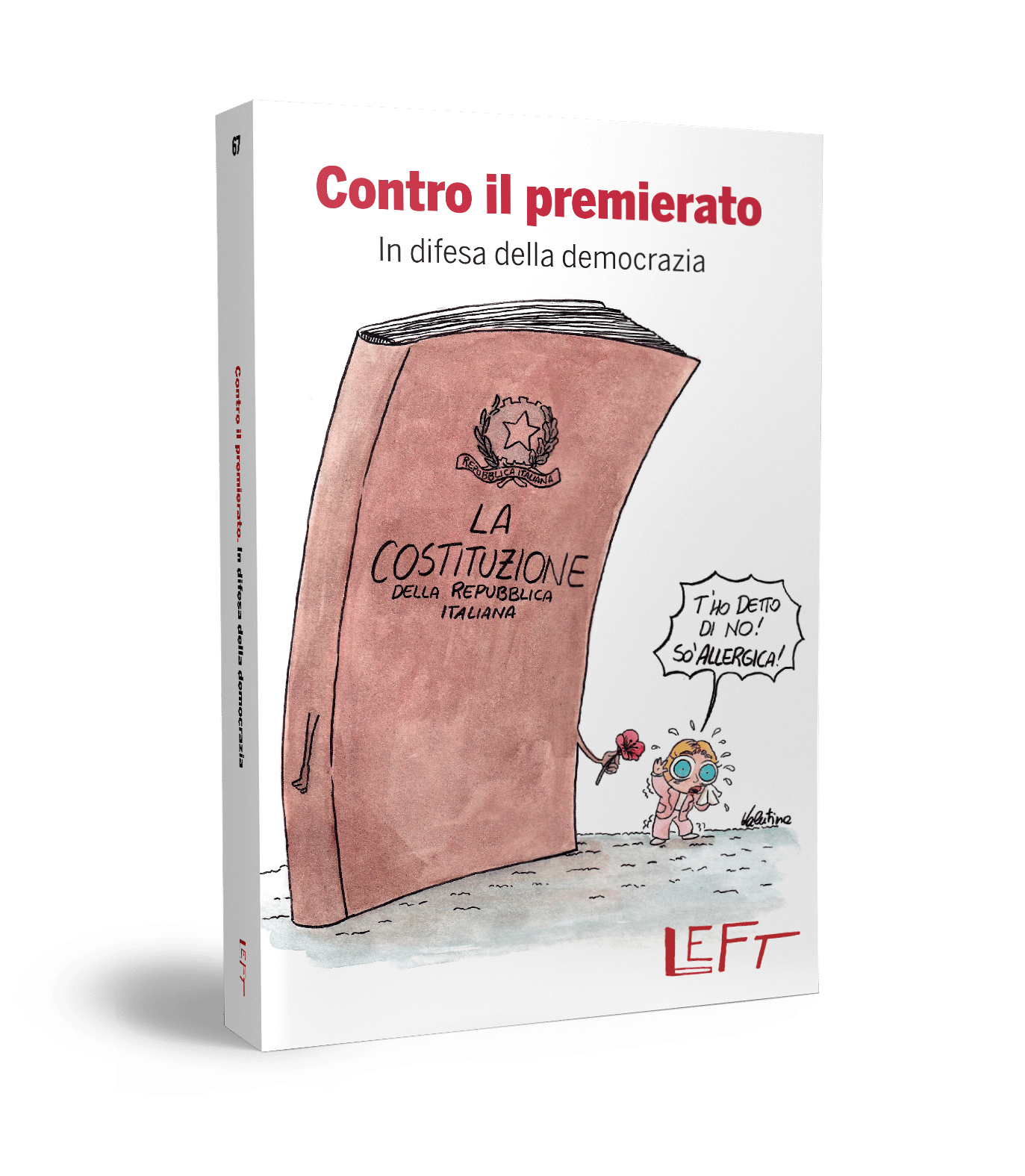

A vote to implement the package of reforms agreed with Brussels may now help to appease the turmoil in the markets. It has at least secured the resignation of prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who had pledged to step down once the package had been passed. The end of the long reign of the much discredited tycoon-turned-politician is the real silver lining in the country’s financial storm.

Italy and Europe can now look forward to a new administration expected to be led by Mario Monti, a former European Commissioner. It must show competence and leadership to help rebuild confidence among investors and allies. Just as importantly, it must contribute to restoring Italians’ faith in their country’s political system.

To do so, Mr Monti must focus his agenda on two broad issues. The first is fixing the Italian economy. The second is mending the broken relationship between voters and politicians.

On the economic front, the priority must be to implement growth-promoting structural reforms. This means reforming the Italian labour market, which suffers from a dangerous bifurcation between some segments of excessive protection and others of extreme insecurity. The service sector must be made more competitive: so far, the entry of talented outsiders has been denied by powerful insiders. Finally, the tax system should be changed, so that the country’s fiscal burden falls more heavily on assets and less on labour.

The government must also continue in its effort to balance its budget and start to reduce the debt burden, so the market’s confidence can be restored. The pension system should be further reformed and a clampdown on tax evasion enforced. If efforts to cut the debt burden fail, a one-off wealth tax or the sale of selected state-owned assets should be contemplated.

The new government must also build a bridge between voters and politicians. A first step would be to take the axe to the exorbitant costs of the Italian political system. A second would be to change the electoral law, allowing voters to have a real say in choosing their MPs.

These reforms would pave the way to a return to the polls, in a country which will, hopefully, be less worried about its future. This is the dimmest aspect of Mr Berlusconi’s legacy, which the new government must help the country to overcome.