The European Parliament’s conflation of Soviet Communism and Nazi-Fascism, says more about the present paranoia surrounding populism than it does about the past. This distortion of history should be of grave concern for democrats across the political spectrum.

After a year of diplomatic back-and-forth, the official history of the Second World War has been re-written. On 18 September the European parliament passed a resolution on ‘the importance of European remembrance for the future of Europe’ to replace previous political statements on human rights in relation to that conflict. The motion, B9‑0100/2019, was conceived as a spirited statement against all forms of political extremism. Glossing the language, it sounds more than reasonable at first. The text reaffirms “the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law” while calling on all EU institutions “to do their utmost to ensure that horrific totalitarian crimes against humanity are remembered” and “guarantee that such crimes will never be repeated.”

One has to ask though: what does this new resolution really add to the continent’s political mythology? The EU already condemns totalitarianism through numerous memorials and rituals, such as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism each 23 August, as well as lending its support to the diverse commemorative traditions of the various member states. Resolutions confirming such commitments, like B6‑0171/2009} RC1, have been in place for over a decade. The reality is, on closer inspection, that this latest text, is not the neutral, democratic eulogy that it presents itself to be. For all its apparently admirable sentiment, a deeply problematic form of historical revisionism lurks beneath the surface.

“European integration has, from the start, been a response to the suffering inflicted by two world wars and by the Nazi tyranny that led to the Holocaust, and to the expansion of totalitarian and undemocratic communist regimes”, reads the text. Is it really fair, though, to draw such swift comparisons between Nazism and other authoritarian systems of the modern era? The resolution is undeniably correct in its assertion that “Nazi and communist regimes carried out mass murders, genocide and deportations and caused a loss of life and freedom in the 20th century on a scale unseen in human history”. Treating the two as equal, though, particularly as regards the unfolding of the war itself, is to grossly oversimplify the history of that period and, ultimately, the continent’s return to peace.

There are several factual distortions in this documentation. This resolution states that the war was “an immediate result” of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the tentative agreement made between the Nazi and Communist forces in 1939 to divide up the continent into two spheres of influence. This was indeed a key moment in the road that led to the conflict; the condition for the initial invasion of Poland. The parties involved, though, had quite different motivations. Hitler, for one, had been planning the expansionist conflict since the 1920s. For Stalin, meanwhile, this was essentially a defensive manoeuvre to protect the USSR from the perceived threat of invasion (and was hotly-contested by many European communists.) The Soviets, in other words, collaborated with the Nazis, thus paving the way for Armageddon.

It’s telling, though, that the text fails to mention other dubious agreements between Hitler and western capitalist powers. It was, after all, Britain and France who agreed to drop the ban on German arms production, as outlined in the Versailles Treaty, and who handed the Nazis strategic territory in Czechoslovakia in 1938 to provide a blockade against the spread of communism.

There are other more glaring omissions. The gravest, perhaps, is the absence of any recognition that the EU’s very existence was made possible by the military campaigns of both the Red Army and other communist affiliated groups. The Nazis were not defeated by a roster of liberally-minded and benevolent democrats as some nostalgic films, like Christopher Nolan’s recent Dunkirk, have presented it. The victory, as most Europeans learn at school, was thanks to the Yalta Agreement, which saw a reluctant alliance not between the Soviets and Nazis, but between the Soviets, British and Americans. Yanks and Tommies played their part, yes, but so too did the millions of Russian soldiers who died on the eastern front, not to mention the Italian, French and other partisan movements, most of which were motivated by some vision of communism.

None of this should be interpreted as a defence of Stalinism. The horrors of Soviet Communism are well known, and the casual manner in which the symbols and language of that era continue to be wielded by some on the left is problematic to say the least. It needs to be recognised, however, that communism has a quite different meaning in Poland than in France, in Romania than in Italy; and neither are these meanings fixed within such geographical confines. In many parts of Europe, communist ideology has long been mixed up with philosophies of anarchism, socialism, liberalism, and, so, democracy. This, after all, is the biggest differentiating point with Nazi-Fascism. Communism has manifested itself in totalitarianism, but it has also been an active agent in civil society. It has been a form of state-based oppression, but has also played its role in a pluralistic conversation about social justice, and as such has deep links to democracy in a way that is simply not true of far-right ideologies.

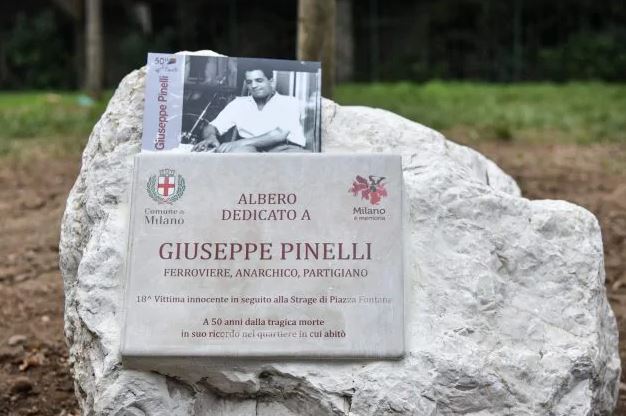

The Italian case is a good example of this. From the 1940s to the 1980s, the country’s communist party (PCI) was the largest in western Europe. The ground movement, made up of many anti-fascist partisans, was broad and encompassed an astounding array of factions with different views on what that particular form of leftist politics meant. Many of these groups condemned the experiment of the USSR – particularly following the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 – and emphasised bottom-up worker-led transformation. The PCI also played a leading role in writing the Constitution of the Italian Republic, a document which, among other things, protects “inviolable” personal liberty, guarantees the right to assembly, forbids censorship of the press, and “rejects war as an instrument of aggression against the freedoms of other peoples and as a means for settling international controversies.” Conflating the energies which led to the authoring of this powerful democratic text, with Nazi-fascism isn’t just wrong, then, it’s a contradiction in terms.

Conflating the energies which led to the authoring of this powerful democratic text with Nazi-fascism isn’t just wrong, then, it’s a contradiction in terms.

As the civil society organisation Libertà e Giustizia put it in a recent communique:

By voting in favour of this resolution, the Italian PD [the centre left] has, in fact, agreed to negate its own history, cancelling its inheritance from the Italian Communist Party, one of the forces from which they were born, and which, among other things, contributed not only to liberating Italy from Nazi Fascism but also to writing the Constitution of the Italian Republic with which they nominally identify. What will these so-called democrats say going forwards? Will they now say that they live in a country where the Constitution is a reflection of totalitarianism?

This paradox – of a democratic, anti-fascist constitution being treated as an apologia for authoritarianism – is a fine illustration of the most absurd implications of this resolution. This, of course, is what happens when one messes around with history. Lies and oversimplifications inevitably give way to tautology and, eventually, a breakdown of reality itself.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of this whole affair, though, is that the EU’s claim to be a bastion of peace has always been one of the strongest arguments for its existence. Resorting to propaganda – in which a ‘pure’ centrist democracy has resisted generic opponents on left and right – clearly says more about Europe’s current struggles against populism than it does about history itself. B9 0100/2019 claims to be founded on the idea that “memories of Europe’s tragic past must be kept alive, in order to honour the victims, condemn the perpetrators and lay the ground for a reconciliation based on truth and remembrance.” By so flagrantly undermining these exact commitments, however, the resolution does the European project, and all of us who still believe in it, a great disservice.

www.opendemocracy.net, 3 ottobre 2019